Uber den Künstler

Gabriel Argy-Rousseau was one of six glass artists who mastered the technique of " Pâte-de-Verre". These other five renowned artists are: Henri Cros (1840-1907), Albert Dammouse (1848-1926), Francois Décorchemont (1880-1971), Georges Despret ( 1862-1952), Amalric Walter (1870-1959).

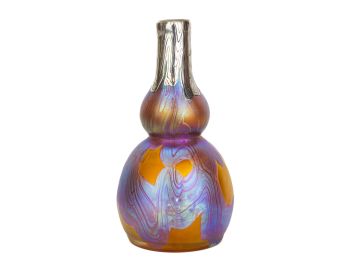

Born Joseph-Gabriel Rousseau, in a small village outside of Chartres to a farming family, Rousseau became interested in drawing at a very early age. He was also intensely interested in physics and chemistry, first attending Ecole Breguet, and in 1902 Ecole de Sèvres, where he met the son of pâte-de-verre pioneer Henri Cros. Following his graduation in 1906, Rousseau took the title of “engineer-ceramist” and worked in a research laboratory developing dental porcelain before devoting his focus exclusively to the art of pâte-de-verre. In 1913 he married Marianne Argyriadès, a highly cultured woman of Greek descent who fueled Rousseau’s interest in Greek and Classical art. After his marriage Rousseau added the first four letters of his wife’s maiden name “a-r-g-y” in homage to her cultural, emotional, and domestic support, signing his name “Argy-Rousseau” for the remainder of his artistic career.

Argy-Rousseau began exhibiting in 1914 at the Exposition du Salon des Artistes Français and quickly gained success and fame due to multiple enthusiastic reviews of his work. In 1921 Argy-Rousseau met gallery and glass works owner Gustave Moser-Millot and established the Société Anonyme des Pâtes de Verre d’Argy-Rousseau. The firm developed their pâte-de-verre technique for 6 months, built extensive new workshops and furnaces, trained 20 workers, and in 1923 began producing regular commissioned work.

The Galerie Moser-Millot held the exclusive rights to exhibit and sell pieces by Argy-Rousseau, though he never divulged the procedures for making pâte-de-verre and retained exclusive rights to his techniques. Moser-Millot acted as the chairman of the board and Argy-Rousseau became managing director, guaranteed a base salary and percentage of annual profits. The pieces were widely distributed across Europe, as far as Romania, to North Africa, the United States, and Latin America. Argy-Rousseau advertised his wares and techniques in French and American Decorative Arts magazines and educated the purchasing public with leaflets describing the technique sufficiently enough to build appreciation for the skill required.

His pâte-de-verre was immediately recognizable for its technique and highly individualized decorative style that was apparent even in his earliest works exhibited in 1914. As was the ideal of the time, and Argy-Rousseau’s own inclinations, nature was the foremost theme in his work. Flowers, insects, animals, and the female form were abundant. He was also inclined to simplicity and balance hallmarks of the Classical art and antiquity that inspired him. In many of his vases he created a frieze out of flowers that wrapped around the upper portions. From 1917 onwards his naturalistic forms became increasingly elongated and the influence of Japanese art became more apparent. Scenes from ancient mythology, such as his famous “Le Jardin des Hespérides” were also common motifs. Expertly skilled at placing glass paste inside the mould to achieve desired effect, the glass ranged in thickness and from semi-transparent to opaque in accordance to the design.

Argy-Rousseau was also an avid inventor, filing several patents during WWI intended to benefit the Ministry of Defense. Of his peacetime discoveries the ‘procedure for instant color photography’ presented to the Académie des Sciences in 1925 earned him a silver medal from the Société d’Encouragement au Progrès and another from the Office National de Recherches Scientifiques et Industrielles et des Inventions. Though his discovery was remarkable, he lacked the financial support to market it. However such an invention showcases how up-to-date Argy-Rousseau was on the era of communication that was dawning. Experiments in the form of pâte-de-verre focused on achieving different effects with the technique and creating a semi-industrialized process. The nature of pâte-de-verre did not lend itself to industrialization and machine production. The destruction of the mould required for completion, variation in height, thickness, and color of the glass, and inability to view the glass during the firing process was labor intensive and expensive. However Argy-Rousseau was able to streamline the process, using master moulds that could be used to easily produce moulds for use in firing, and craftsmen to execute aspects of the process in an assembly line fashion. Argy-Rouseeau was the master craftsman of the factory, overseeing every aspect of the process as technical and artistic director.

Despite Argy-Rousseau’s initial success and advances in time and money saving techniques, the financial crash of 1929 severely deteriorated the market for luxury glass. Argy-Rousseau, acting on the advice of clients, tried to completely redesign the models for vases, bowls, lamps, and other objects, yet he was prevented by Moser-Millet. In turn, Moser-Millet ordered Argy-Rousseau to produce religious objects, which were not financially successful and which the artist was not proud of, refusing to sign his full name on completed pieces. As the depression deepened and unsold pâte-de-verre piled up in the factory, Moser-Millot, closed the factory on December 31, 1931. The Société Anonyme des Pâte de Verre d’Argy-Rousseau had existed for exactly ten years.

In July of 1932 Argy-Rousseau bought what little he could afford from the factory liquidation and established his own studio on the Rue Cail. He worked independently, calling on collaborators only when necessary. Despite the animosity between Argy-Rousseau and Moser-Millet following the liquidation of the factory, he was contractually obligated to continue displaying his works at Moser-Millet’s gallery. Argy-Rousseau began producing new products using techniques he developed. These included ‘sculpted pâte de verre enamels’ which eh produced in a very limited quantity between 1932 and 1934 and ‘cut pâte de cristal’ from 1934 to 1937. Pâte-de-verre was no longer commercially successful and he began working primarily with enameled glass. Unfortunately the art glass market of the time was dominated by the opalescent or tinted glass that was produced by firms Daum, Lalique, and Tiffany Studios in vast quantities and sold at lower prices.

Further difficulties faced Argy-Rousseau during World War II as he was unable to find raw materials and fuel to fire the kilns. He was forced to take a job at a commercial porcelain factory, similar to the one he had started his career, and was able to perfect the manufacturing process for the factory. Despite this industrial success, Argy-Rousseau remained deeply in debt and the Société des Artistes Décorateurs threatened to revoke his membership for non-payment. On top of his financial troubles Argy-Rousseau was suffering from a painful heart condition. He died on January 20, 1953 and was eulogized by a small group of loyal friends.